#279: The Process(es) of Analytics (We Have Thoughts)

What is “process” in analytics? On the one hand, it can be seen as a detailed sequence of minutia by which anything that needs to be repeated in the world of analytics gets carried out in a structured and consistent manner. On the other hand, that’s the sort of definition that strikes terror and rage in the hearts of many souls. Some of those souls are co-hosts of this podcast. Even the <ahem> more process-oriented co-hosts bristle at such a definition (but for different reasons). So, what ARE some of the core processes in analytics? And, what is the appropriate balance between establishing a prescriptive structure and leaving sufficient flexibility to allow human judgment to adapt a process to fit specific situations? Those are the sorts of questions tackled on this episode, which was released on time with all of its underlying component parts thanks to a reasonably robust…process.

Links to Resources Mentioned in the Show

- Analysis planning template (let us know if you use or consider using this one; we’re curious, as it’s come up on the show before!)

- The framework about which Moe was relentlessly grilled:

Episode Transcript

00:00:05.75 [Announcer]: Welcome to the Analytics Power Hour. Analytics topics covered conversationally and sometimes with explicit language.

00:00:14.22 [Michael Helbling]: Hey everybody, welcome to the Analytics Power Hour. This is episode 279. Process. It’s just a series of actions taken to achieve a particular result, but somehow it can become so much more than that in good and bad ways. A good analyst can tell when the same problem pops up over and over again in their work and they’ll do something about it. And that sometimes there’s not enough process in that case. And alternatively, you might exist in an environment where there’s too much and you work endlessly and never know if you had any impact or meaning. So, I don’t know, let’s focus on the just enough part and try to make our work the best it can be. And that was part of my process. Let me introduce my co-hosts. Moee Kiss, how you going?

00:01:06.70 [Moe Kiss]: I’m going great. Thanks for asking.

00:01:09.75 [Michael Helbling]: Oh, it’s so nice to be able to ask you how you’re going, because I ask the other co-hosts, and they don’t understand what I’m talking about. It’s fair. Good. And Val Kroll, hey, how you doing?

00:01:22.64 [Val Kroll]: Pretty good, Michael.

00:01:25.23 [Michael Helbling]: Da’ bears. It’s been a dream. Well, no, I’m trying to do a Chicago greeting, but, you know,

00:01:33.51 [Val Kroll]: I like it.

00:01:33.93 [Michael Helbling]: And then, of course, Tim Wilson, howdy partner. I’ll do. Wow. Julie Hoyer, go Browns.

00:01:43.32 [Julie Hoyer]: Oh, go Browns.

00:01:45.04 [Michael Helbling]: Come on now. I’ll take it, I guess. Hey, I’m a Browns fan. All right. Let’s dive into this process discussion. I think, you know, Julie, I want to start with you because I think this was your idea. What? What it was.

00:02:03.36 [Julie Hoyer]: I don’t remember that. I believe so.

00:02:06.05 [Tim Wilson]: Let the record show. Let me check the notes from our process.

00:02:09.44 [Michael Helbling]: We have a process for this. We recorded this. But I think, you know, you know, As we look into this sort of thing, like talk to a little bit, kick us off a little bit about where you’ve seen process maybe not work so well or not where a lack of process has affected you and your work. Maybe let’s start with that and then we’ll kind of like wind up from there. Oh, wow. Or if you prefer to do positive, you could give an example of where you saw a great process work and you could be like, oh, I’m so awesome that I created this amazing process, but I was gonna let you save that for later in the show.

00:02:48.63 [Val Kroll]: Problems then solution.

00:02:51.28 [Michael Helbling]: Transformative narrative arc for your character in the podcast.

00:02:58.13 [Julie Hoyer]: All right, well, to open this up, I guess my first thoughts on process. I will say it’s been interesting because every client I work on, our process is slightly different. You’d like to think we set up a repeatable process and we’re going to come to a conclusion that this is really effective and we’re just gonna keep rolling with it. But every client brings kind of their own process to the table. So I will say that I am really excited about this discussion because I’ve seen it where certain clients have a ton of process and it just slows us down immensely or they want to automate a lot of the process like do everything asynchronously and you know you have to have a lot of technology and tools and logins and interfaces to like communicate between us and their team and it’s amazing how like they’re trying to do it for effectiveness and clarity and it slows us way down and I think a lot of times It burdens us where we lose the ability to have like a personal relationship with them. And then on the other extreme, when there’s no process, it does feel like you’re kind of like flying by the seat of your pants. And sometimes it’s a little chaotic. So I’ve definitely seen the gamut, the spread.

00:04:15.83 [Moe Kiss]: Sorry, Julie, when you say no process, Can you describe what that looks like? Because I also like a minor process would probably look quite different to your experience like working with different clients. But what does a client with their process look like for the team?

00:04:32.43 [Julie Hoyer]: Ones that don’t really love even like a weekly cadence touch point, they’re like, we’ll reach out when we want to reach out and you get like the chaotic random email. And then the team is scrambling and it’s a little unclear who you’re exact, you know, direct stakeholder. Some of them are like, oh, well, I told my coworker just to directly email you. And we’re like, we don’t know who this is. Are we allowed to pick this up and do it? Can we schedule time with you? I now have to loop back with the stakeholder. So that’s kind of my experience of what I’d call no process.

00:05:06.18 [Tim Wilson]: I mean, it seems like there’s from like an analytical intake, there are cases where Like to me, one extreme is when it’s assuming you have, this is a person who I am supposed to address their needs as an analyst. So we are going to meet and have a conversation and I will uncover the requirements and the need and the underlying problem and we’ll kind of conversationally, kind of process free, gather the requirements and then I will go back and and execute. That’s like no process and it’s efficient or low process and it can be efficient. The kicker is that when you roll with that and you have different people not necessarily having enough of a discussion and then something gets missed, a timeline isn’t communicated or a scope or a timeframe, I’ve seen it start to swing in the other direction. It’s like, well, now when you meet with a, sure, sure, sure, we still want you to meet with the stakeholder, but here’s the form. And you got to make sure that everything on this brief or this intake form or whatever it is, is sort of filled out. And there are times where it gets to like, but some of this stuff isn’t relevant, but it’s a required field, no matter what that intake is. And it tries to make the process, and I’m thinking specifically on kind of, analysis projects intake, not necessarily implementation or others. It can get to where, well, now you’ve removed judgment because you said, well, we had one issue one time. Let’s now inject more structure into the process. And that’s how processes become bloated, because you’re trying to say, well, we want to keep shedding every possible crack. And now we’ve built something that is a cumbersome formulaic way to do something. So those are on my two extremes.

00:07:02.48 [Julie Hoyer]: If the other side is we got to talk about every single thing, and it’s very super organic, and we have nothing, quote unquote, like repeatable, like if that’s the spectrum, I’m going towards the secondary one, like the more organic. I don’t know if that’s right, but I definitely prefer that over the like, oh my God, if they’re like, we wanna work with you and Jira, we’ll just send you tickets. I’m like, get me off this flipping project, I’m done. I hear those words and I’m like, mm-mm, no, no thanks.

00:07:30.83 [Michael Helbling]: I have a saying, I say just enough process and no more. So it’s just as much as you need and not more than that.

00:07:40.51 [Moe Kiss]: But how do you know you’ve hit that?

00:07:42.38 [Tim Wilson]: You don’t. But that’s that’s like saying, building a motto and saying, you’re going to have type one and type two errors, right? You’re going to have cases where you have too much. If I still like it, it’s it’s okay if I don’t like it too much.

00:07:56.21 [Val Kroll]: Super objective.

00:07:57.01 [Tim Wilson]: Scientific. Yeah, it works. Well, that, I mean, that does remind me, I mean, the quick example, and this wasn’t a client. This was somebody who we were talking to for quite a long time about potentially being a client, the head of analytics, and they had gone down the Jira ticketing process because they felt like their team was having spent too much time having those organic conversations. So it’s like, it’s a logical understatement. It’s a logical step to say, oh, we’ll make this asynchronous and put a form in. I’ve been for years. I think those always end up in the same spot. And this is where this company was living in that they were just dying death by a thousand cuts because they were just getting requests lobbed at them and people were getting them in as fast as they could because they knew it was going into a a queue and they were trying to turn something into this machine that shouldn’t be a machine. And he’s like, we’re just overloaded by these requests and every request we get that comes in, we’re going to have 10 iterations of back and forth before we’re actually done with the ticket.

00:09:08.76 [Moe Kiss]: But isn’t that, okay, I have been like, doing some serious soul searching on both planning and processing, because I am definitely, Julie, when you describe the very non-processing world, that is like my mecca where I live and operate, and it is not… By choice. Oh, the Colomé Colomé.

00:09:32.11 [Michael Helbling]: I think there’s a personality component to it, for sure.

00:09:35.31 [Moe Kiss]: But the thing that I have been grappling with is I think that there is a process component and process is such a loaded word. But I’m particularly thinking we’ve said this multiple times now, like, tickets going in and they go in a queue. That to me is not a process. That to me is a way of working, which is not a way of working that I want. And so JIRA can be a way that you can manage tasks. The problem is when that then becomes, this is how we engage with our stakeholders. I violently hate this whole service desk mentality. I believe in data folks being business partners and I do not think submitting tickets. Actually, it’s the right way of working, even if you want to use tickets for task management. I’ve always said team leads can decide if they want to use JIRA or any other task management. I don’t give a shit. It’s not my thing. We’ve now agreed as a team we’re all going to use it. But it is more about us as a team being able to make prioritization decisions than stakeholders thinking, anything I asked where it’s going to get done, it goes to the back of the queue, I can just ask for whatever the fuck I want, even if it’s going to add no value. But I’m still processing a list.

00:10:58.10 [Tim Wilson]: That’s a good point. That’s the tool for being used as an intake as part of the intake process or as a tool within the resource management and availability and prioritization process.

00:11:12.91 [Val Kroll]: I was going to say, well, I was going to admit rather that Hi, my name is Val Kroll and I’m a recovering implementing tickets in front of my analytics team person, but I will say, and Tim and I actually went a couple rounds on this over dinner one time when we were on site with the client, I do recall.

00:11:30.94 [Tim Wilson]: I think there’s trauma with a couple of, yeah.

00:11:33.22 [Val Kroll]: With the capital T. Yeah. Some other people who had tickets to that show. Yes. But what I realized was, well, so contextually, I was standing up a program for the first time ever. And so there was also like a lot of novelty to the data that was now available. And so there was a lot of like, This would be interesting or could you tell me if questions right and so when i was putting that system in place what i actually realize now years later is i was actually itching more for. It was only however many minutes into the episode before we said. the analysis planning document, the one that Julie that I referenced. This is probably the sixth episode where I’ve referenced that thing. And so the analysis planning document, for those who have not had the pleasure, we will link it again in the show notes. It talks a lot about what is needed from this analysis, right? Like putting some boundaries around the hypothesis and timeframes and just kind of really getting a broader understanding and kind of asking the business partner to be thoughtful about exactly what they’re looking for and like, how is this going to help them support them? There’s a meeting coming up, whatever. So I wanted some of that documented to help foster the conversation that always happened before we picked up a ticket. So to your point, Moe, about like interfacing with your stakeholders, it never replaced a thoughtful conversation as a partner. But I have to admit that I definitely was like, oh, this is how I’ll operationalize this team. Because I had people growing my team. It was just me at first, and then it was four of us. And I was like, how do I manage this? I’m not touching all these stakeholders. So for everyone out there who’s done it, just know that there’s another side. We’re not shaming you.

00:13:22.43 [Michael Helbling]: Hey, quick question. When was the last time you really unplugged? Like inbox zero, phonon do not disturb, toes in the sand kind of unplugged. With 5Tran, that dream doesn’t have to wait till retirement. Their automated data integration means your pipelines run smoothly even when you’re on the beach with a book in one hand and a drink in the other. 5Cran handles the heavy lifting, syncing your data from all your sources into your warehouse reliably and continuously. No babysitting required. No custom scripts. No last-minute dashboard breakage. Just dependable pipelines to give you peace of mind. So go ahead, take that long weekend. Heck, take the full week. 5TRAN’s got it covered. Visit 5TRAN.com slash APH. You can see an interactive demo, sign up for a free trial. That is F-I-V-E-T-R-A-N dot com slash APH. 5TRAN, data in, decisions out. Moe said something that I think is really important distinction, which is you can have a ticketing system, but don’t use that as the means of communication.

00:14:34.61 [Julie Hoyer]: Yes. 100%.

00:14:35.52 [Michael Helbling]: The communication happens out in another sphere, and then you manage the task, and you can communicate within it. Is this your idea? But there should be layers to this. So your process should incorporate. not just I submitted a ticket, but more like I then connected the overarching purpose for this to it. And then the ticket supports it. If you have a system like that, you put in some intake system for.

00:15:04.17 [Tim Wilson]: Tickets or some sort of atomic or granular management of what is the work that we’re doing has a lot of value when you look back at the end of a quarter, the end of a year. I mean, that I’ve seen as well where it’s like the team keeps growing because it’s just emails coming in. And when somebody says, what do we actually do? And it’s like, well, let me go through the network drive folders and let me sift through my email. And all of a sudden, now you’re not generating good data on the work that you’re doing. Not that you’re just trying to count volume of work, but sort of forcing you to think about the nature of what types of work you’re doing, who you’re doing it for, what value it delivered. All of that goes towards having a data orientation, I think, to the work that’s being done. I know I fall on a weird extreme on many dimensions, but it’s like tracking time. Even when I have not been working somewhere that I’ve been required to track time, even when I wasn’t working at all, I was tracking time. But I was shifting that around to No one’s saying anything. I just think no one’s like, there are some facial expressions. That sounds normal. But whether it’s, yeah. So, I mean, maybe not. I mean, there’s teasing. Well, I’ll stop.

00:16:35.87 [Val Kroll]: Oh, no. Why did you do it? We’re just giving you a hard time.

00:16:41.48 [Tim Wilson]: Well, I’m tracking time because I will go back and say, this feels like this is taking an enormous amount of my time. Is it? How often am I doing it? I have to have that information somewhere. I mean, there have been cases where there have been time tracking that’s enforced purely for billing clients. And that doesn’t actually tell me some of the non-billable stuff that I do that I actually do want to know. I spend a fair amount of time on a podcast. I spend a fair amount of time on a local meetup. I spend, I don’t, not all parts of my life, there is kind of a professional, personal boundary. I’m not, not tracking like, you know, quality time with my wife.

00:17:23.22 [Val Kroll]: And non-quality time with your wife, you flip it.

00:17:26.04 [Tim Wilson]: Non-quality time, yes. Two different tasks under that project. different codes, yeah. But I think when it goes in, I mean, maybe like Moe, how do your, it sounds like it’s kind of delegated to your team, but when it comes to the work, there’s always going to be more work that could be done than can be done. And when it comes to prioritizing and managing and that’s Always going to be shifting. The priorities today are going to be different than tomorrow. Like how do you see that as a process by which the team doesn’t just get run ragged and what to look like?

00:18:10.19 [Moe Kiss]: Yeah, so I’ve been taking feedback on this and trying to improve. So there’s been lots of really robust conversations probably since about, I don’t know, maybe three months ago. And so what we’ve decided for the second half of this year was to do very rigorous planning. So a lot of data folks at Canva are more embedded in product teams. And so it’s kind of easy. You have a product manager. We have technical program managers who help with this sort of stuff. In marketing, we kind of like. run to the beat of our own drums, so it’s a bit unique. And we were just like, you know what, we’re going to really throw everything at the wall here and see what are all the things that we know that we need to do basically in half two, what are the things we want to do, all that sort of stuff. And so our planning cycle was really intensive. And then we broke it down. We had some big buckets and themes of work that we wanted to do for different areas because we have one team that built tooling and some that are doing more strategic analytics and that sort of thing. And then we bucketed it all out. We had to do some really ruthless prioritization because we do have some teams that are just under resourced and it’s taken too long to get headcount and things like that. And we went to our stakeholders and were like, this is what we’re planning for H2. Every time you come to it, like this has all of the things you’ve asked us for, by the way, already baked in. And anytime you come to us in H2 and you ask for something that’s not on this list, we’re going to ask you to cut something else from it. And like, I mean, we had one team where we had to cut like 50% of their work just because of headcount stuff. And so we went through the stakeholder and it was, yeah, highly entertaining because sometimes stakeholders don’t realize that they’re the problem. They’re like, oh, but like, just tell me when the team is asking for all this ad hoc stuff. And I’m like, that would be you, but I can’t really say that quite so directly. But I think the thing that we’re really trying to shift, like I said, I’ve always felt like data is like a partnership model. But it’s like, we’re not going to prioritize on your behalf. We’re going to do this together, and we’re going to come up with a list. And so then therefore, when you want something else, that’s OK. And we will happily do that, but then we need to drop something else. And I think the thing that I’ve probably most enjoyed about it, which the team are pretty good at, but it’s kind of solidified it, is even some of our teams that are like a super ad hoc and reactive, which is like the nature of their work, have gone through this process now and really been able to kind of give more thought and color to the things that they’re doing that might be helping them with like a promotion or like, like these are the projects that I want to be working on as part of my growth and development plans. And like, yeah, it’s fucking annoying, but like apparently doing process stuff is like good.

00:20:53.69 [Tim Wilson]: Well, so in that specific, because what I feel like I’ve run into at time, like they’re typically there’s just for simplicity, say there’s one analyst and they’re supporting a team that has four people and a manager on it, which is super, super simplistic. And that sort of prioritization is done. But the fact is, is the two different people on that team, but more often than not, it’s like two other groups or sub departments, they have their priorities. You know, and so when somebody comes in and says, but this is really burning. And it’s like, well, what are you gonna, you can’t just ask them what you’re gonna drop. Cause they could say, well, yeah, drop that thing for that other group. Cause I don’t give a shit about it. I mean, they not overly, but they don’t like, do you have to, if that sort of cutting something happens, this is where I’ve never found the great way to do it. Do you have to keep going up the chain and keep pulling in some more senior person to say, Your team isn’t capable of making this judgment call. You’re going to have to step in until person X, that their thing’s getting cut because person Y’s thing now supersedes it.

00:22:05.56 [Moe Kiss]: Column A and Column B, like generally like a team lead does have a relationship with the like court and court manager, like in this hypothetical situation, there’s four people. So they could be like person X’s thing is more important than person Y’s. But the reality is, the manager, in most cases, is like, actually, my thing that’s item A is more important than either of their two things. So I don’t give a shit about those. And that’s what we’ve started to work towards, because I think we did also really have that other format of trying to please person X and person Y. And it just doesn’t work, because you end up building stuff that is very like or or doing analysis that’s very bespoke and it serves one person and like I think the biggest like shift in our direction is being like if it is for one person ad hoc non-repeatable like not connected to a company like we’re just we’re saying no it has to serve as multiple teams multiple groups it like we when we build it we want to build something that’s reusable or could be like adjusted for a different use case I don’t know, but I feel like I’m like preaching to the choir.

00:23:11.08 [Julie Hoyer]: At least for me, I’m working with smaller stakeholder groups where with you, like you’re kind of seeing the whole like beast of it. Like your scale of the team you’re talking about is so different than the scale of team I work on, even if you count my stakeholders plus my internal teams, you know what I mean? So it’s, I was really curious to hear how you guys do manage that to Tim’s point.

00:23:35.00 [Michael Helbling]: Well, and I think in smaller or less-scaled organizations, Moe, what happens is people haven’t faced that actual boundary. And so they’re still trying to do all of the one-offs as if they were just as important as the structural or multi-team or business strategy-focused types of work. And there’s nobody giving any delineation between Okay, this is sort of like a nice to have versus a must have and they seem equally important and people are getting run off their feet and burnt out completely in organizations that aren’t trying to make those distinctions because analysts are just trying to do everything for everybody, which there’s an unending amount of interest on specific topics that may or may not actually have any worth in terms of like the time it takes to go and pull the data together, do the analysis, present it back.

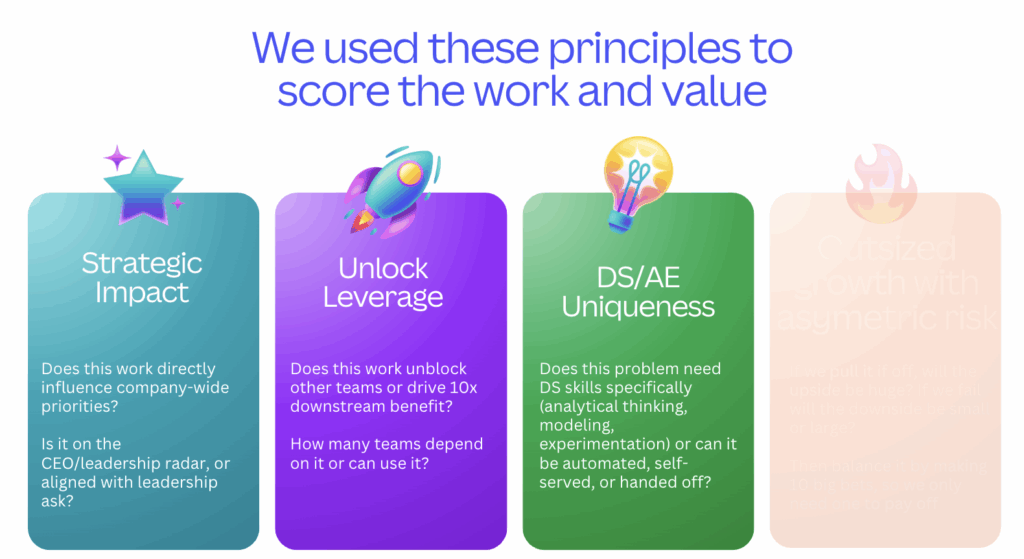

00:24:32.25 [Moe Kiss]: I did actually come up with a framework, which I shared with the team, and I’m happy to share in the share notes afterwards, of when we came up with this whole body of work of things that we need to do in H2, we actually scored every single thing on there. And one of the most strategic impact, one of them is, I can’t remember the name. It’s like multiplying effects. So is this servicing one person or a team of people? And the last one, which actually became the most important, I called DS uniqueness. So we would score it a one if a marketer could pull the report themselves if they really had to. I would market a five if it’s building an MMM and it’s doing QA on the data coming from this platform. And only a data scientist can do that specific task. And so we had this kind of and we’ve shared it with the team now and then like when you get something and you do the eyeball check and you feel like this task is like sitting at the ones you shouldn’t be doing it. It should be sitting at like three plus across all those three different pillars and like that’s kind of how we’re trying to think about like I said. I’ll let you know in like a year if I still have a job.

00:25:45.08 [Michael Helbling]: How do you score it if the question is, will the CEO wants it?

00:25:48.63 [Moe Kiss]: But that’s strategic impact. And that’s actually one of the criteria of like, has like a founder or an investor asked for this, or is it connected to a company level goal? And then you would score that like a five, because yes, that does have huge strategic impact and that thing that we need to do.

00:26:03.78 [Tim Wilson]: To me, that is having gone through various, I mean, going back years, having put in the scoring, I’ve always thought the scoring is like, you need to figure out, you kind of need to run organically with people that you know and trust and are kind of thinking about the business. And then what you’re trying to do is just enough, not too much, Michael, kind of codify that and say, what really are the decision points? And it’s like that strategic one is always gonna crop up, and then I do think there’s a part of it that says you have to run it and have the discipline to say six months or a year down the road, is this working? How are we ourselves gaming the system because we’re bumping up the score here because we just know this thing needs to happen? Even when you do the scoring, presumably you’re not saying, and then you get the score and we sort and chug away, it’s like, that’s a way to, I love the way you just framed it. Like if you’re eyeballing it and you’ve got ones and twos on stuff you’re working on, you need to kind of stop and ask why. And it may be, oh, I’m falling back into a bad habit, trying to keep the squeaky wheel happy, or it may be, no, these really need to be done and this framework isn’t capturing it. And we need to kind of make a note of that and refine our process, right?

00:27:24.12 [Julie Hoyer]: Does scoping come into it at all Moee or is that like note you use the framework you talked about? Yeah, because I’m just thinking like what if you do identify like the top five things that really have to happen in this team like these are things that would be the best for them to tackle. But then you get to actually scoping it and this amount of work and your capacity to do the work and it’s not going to fit in the time period that like is realistic so then is that like a secondary part of you guys after you’ve done your intake and priority then it’s scoping in like another round of prioritization or is that part of your to be fair it was a little complex because we did agree that we did have a

00:28:08.47 [Moe Kiss]: I think we had a time estimate, but they were very rough. Also, because we’re trying to plan out work for such a big team over a six-month period, we were also talking about tasks in days and weeks or hour blocks. There was a component of that, but then it would be more about if something scores really highly and this person or this team doesn’t have capacity for it, but we know that it’s on our list to do. How do we move resources or that particular task to a different team to make sure we can cover it?

00:28:39.32 [Tim Wilson]: Can we shift to what happens when it gets… scoped and the scope is, it’s always gonna be low. It’s always gonna undershoot. But when something you get into it and there’s a commitment to we’re going to do this project and then all of a sudden you realize, oh my God, like the day to clean up for this, like we just did not see this hot mess. This is gonna be 4x the level of effort. What’s the process? I’ll say it for getting back to do you just keep plowing ahead? Say we’re gonna suck it up and do it and figure it out or?

00:29:17.19 [Moe Kiss]: Tim, are you asking me the question because like when did this conversation get turned around? Cause like I am not the process person.

00:29:24.84 [Tim Wilson]: And like everyone else- You keep saying that, but you have all this, you have all these thoughts where you’re like, well, here’s the, here’s the mental and actual and reality process step by step, how I approach this, but I don’t like process. Let me tell you about the four-part framework we have.

00:29:42.31 [Moe Kiss]: I also said to my team leads, like, here are some guiding principles, but also I’m sure of this. So, like, I need you guys to lean in and help, and they honestly did a phenomenal job.

00:29:50.53 [Michael Helbling]: I am not the process person. But I think, like me, Moe, you think about process in terms of, like, the value it can create when applied correctly and given to. the challenges that your team is facing. That’s the way I look at it.

00:30:08.88 [Tim Wilson]: Maybe let me side rant on this. I don’t think if it’s process for the sake of process in many organizations, especially larger enterprises, wind up in that world where they’re at a lady working for me who She didn’t care if she delivered business value ever. As long as she followed the umpteen gazillion steps in a wildly overloaded process, she knew that was going to be her way to get ahead in the organization. That’s problematic. I look at, actually, my wife’s Measure Camp New York presentation about process where she’s called out that it is You, there is a process. Now there are levels of how much you’ve codified it and documented, but everyone is following processes all the time. It’s a matter of when an inefficiency is being identified or a problem. And there are lots of, you know, getting into heavy process stuff. There are certainly six sigmen, all those worlds to sort of really diagnose them. But I don’t, I don’t want it to turn around. It’s like, I’m not a process person. Like, no, everybody’s a process person, whether they, realize it or not. Like there’s, I don’t think you can, function, like you have a process. There’s an innate organic, you run into these things all the time and there is a way of reacting to them. It’s not like, well, on Tuesday, today I feel like we’re carrier pigeons can be the way that we, you know, get intake requests. And on Wednesday, you know, what we should do is we should figure out what our business needs, right? So I don’t know, maybe that’s my, my, my side rant is like, recognize processes there. It’s useful to recognize that.

00:31:52.17 [Michael Helbling]: And I think what we’re talking about is expanding the process out beyond the individual. So in other words, you take your process and you push it out across a team or across a function. And you say, OK, this is the way we’re going to execute this all the time. And a lot of times, people like me who say I’m not a big fan of process, it means that I don’t externalize my process well. That’s actually what I’m trying to say is I have a process like you just said, Tim, but my process is sort of like very intuitive. And so a lot of times it’s hard for me to sort of like document that process for you. So you like, if Tim was going to follow Michael’s process, I would have a hard time writing it down so you could follow it step by step.

00:32:34.52 [Moe Kiss]: But I think that’s the like the learning that I’m having and maybe maybe Tim’s right.

00:32:40.87 [Tim Wilson]: We can cut this out.

00:32:45.42 [Moe Kiss]: No, but there is this thing where like I would self describe as a person that’s not really into process. But the thing is, like all of the thinking happens in my head. It’s just not externalized. And so, like you said, I know how all these pieces of the puzzle fit together. And I know why I’m asked Johnny to do X and why Max is working on Y and why Timmy’s tackling Z and Sarah’s doing whatever and great examples. But like, I know why all those things are being done and how they let her out. I think the thing that I’ve really been learning over the course of this year is that’s not fucking good enough. You can’t have all that stuff floating around in your head. Even if that process works for you, it’s not working for my team because they’re like, why does task X Like, how does this fit into everything? Where does this connect? Like, why is this important? Like, oh, this is going to a founder. I probably need to know that. And so it’s about me making sure that I’m like connecting the dots for them is that they have the right information. And that’s like a growth journey. Tim, you said we weren’t going to talk about fluffy feelings today.

00:33:57.68 [Michael Helbling]: Yeah, and I love that mode because that’s exactly right. It’s like anytime you need to transfer something from one person to another, whether that’s vision as a leader, whether it’s analysis from one analyst to another, the production of a podcast, we have a process document. I guess who didn’t write that document.

00:34:17.11 [Tim Wilson]: One, you think there’s one?

00:34:17.91 [Michael Helbling]: We have multiple process documents. To be fair, Val, I’ve never actually looked at them. Outed. I’ve never actually looked at them.

00:34:25.50 [Val Kroll]: Tim, take a drink.

00:34:26.72 [Tim Wilson]: Yeah.

00:34:30.30 [Michael Helbling]: That’s exactly it. If you wanted to make sure that that process continued, you go through those steps and that’s kind of the idea is like, yeah, the value of it is, okay, wow, this person is doing it really, really well. Let’s dive in and see what they’re doing and then expand that out to the rest of the team. And you do that all the time when you look at things like, what’s going well? Oh, that’s going well. Okay, let’s figure out why and then expand on it.

00:34:56.95 [Tim Wilson]: But not to the point that you externalize it to the point that you think now that we have the process, anybody can do it. I think that’s the, I mean, yeah.

00:35:03.86 [Michael Helbling]: Very annoying. Yeah, yeah. Yep. And I think that’s where you get into sort of some wisdom about what’s required in terms of skill and what’s required in terms of steps. And that’s a balancing act.

00:35:22.61 [Julie Hoyer]: And like how much you can generalize a process? I think that’s where you hit the tipping point where people want to generalize a process too broadly. And then it starts to become cumbersome and it’s not applicable. So it’s like the flexibility of, the more you guys were talking to, it’s like there’s layers of process. You have individual processes. You have ones that scale to a small team, a large team. There’s like competing processes. But it does like you have that tipping point of like where is it to burdensome because we’ve overgeneralized or where our processes like intersecting in not a helpful way. Oh, my brain is starting.

00:36:03.94 [Val Kroll]: spin down a rabbit hole. The other thing I was thinking too, and I think this is somewhere along the lines of what you were kind of thinking about the different levels of this, Julie, is that I think a lot of times a lot of things get labeled as processed too. I think we touched upon this already earlier with the ways of working, but Sometimes, processes use, especially clients that we work with, to solve something that can’t be solved with process. If there’s two teams that have two different responsibilities as a part of this input or whatever and they don’t disagree or their motivations aren’t aligned correctly, putting in a process say, you should do this by this day or you have to fill this out as a way to control when really the alignment isn’t there outside of the process. There’s no amount of like, but I put that in an email or that’s in the spreadsheet, did you check that box is not going to solve too. It’s the layers, but then also the things that process tries to get thrown on top of to kind of be a band-aid in certain situations or just to It’s not always actually making the work more efficient or valuable.

00:37:10.06 [Julie Hoyer]: Because Moe, even you saying how you just make those decisions, to me, that’s not a process that anyone else can follow. That is your problem-solving skills, your management skills, your leadership skills. But to your point, the way you communicate it out to people probably could have a very clear process so that they get everything they need.

00:37:28.76 [Moe Kiss]: Out of curiosity, because I feel like we’re saying the P word every third word. And I think it means so many different things to different people. When you think of like the best process that you’ve seen, What does that look like to you? What’s an example of a process that just works really well? I know Val had a really good example, but what about other folks? What stands out to you where you’ve seen someone do something and you’re like, that works?

00:37:58.07 [Michael Helbling]: My problem though is that I’ve always modulate the process for the situation. or the level. So like I work in consulting, so I have different clients and different clients need different levels of process. So I bring that level to whatever that situation is and you adapt. So if you’re working with a company that’s a highly processed organization that you’re doing, much more process around everything in the work. Whereas if there’s a leaner team that you’re working with or a smaller company, You can just have a conversation and then get to work and everybody’s on the same page and it’s fine. There’s a lower level of process. So I tend to modulate mine up and down.

00:38:40.75 [Moe Kiss]: Yeah. So to you, it sounds like adaptability is the key, though, to good process.

00:38:44.59 [Michael Helbling]: Yeah, absolutely. Because if I brought this heavy-handed, multi-step process to a smaller, more nimble team, they would just be like, why are you wasting all of our time with this extra stuff we don’t need?

00:38:57.67 [Moe Kiss]: But why is it wasting time for a small team, but not a big team?

00:39:00.91 [Michael Helbling]: Because you don’t need that level of detail or there’s not that level of complexity. There’s not that many stakeholders with differing opinions. Like there’s all kinds of reasons why you wouldn’t need to bring like all that additional artifacts into it.

00:39:13.36 [Val Kroll]: Can I say, so this is actually, I have one thought that I’m not sure if you’ll agree with this, Michael, but the difference that I’ve seen working in much smaller organizations and then like 100,000 person organizations is that with the adaptability or the scalability I think Michael’s talking about is when you’re in a smaller group there’s so much more that can just be like a soft contract between people because the expectations can be unwritten and when it’s more people there’s more variability or like you have to report things to the FDA or the SEC like then it becomes like the necessity to be more rigorous

00:39:48.06 [Michael Helbling]: Yeah, there’s a PMO and there’s an InfoSec team and there’s a procurement org. There’s all these other interfacing organizations and structures that live in these bigger environments that you have to navigate through. That requires you to have a little bit more structured or refined process that you go through things kind of a step by step. So like, you know, let’s say you’re going to go build a dashboard for somebody. You know, you could sit down with a smaller company that has two or three stakeholders, the chief marketing officer and one of the people on their team. And you spend an hour and a half chatting with them about their strategy, what they’re doing, talking about all their data and those things like that. You go away and you come back with version one of the dashboard a week later. and it’s looking good and you’re on your way. You take that exact same process and the exact same data points and you walk into a much bigger organization, you’re gonna be weeks doing the discovery and the step through and all those different things until you can then get into the people that are gonna house the data and they’re gonna do all the setup of that data and then you’re gonna go to that and you’re gonna get into that team. And so that same dashboard will take six times as long, maybe longer, to build in that environment just because of the additional process steps you need to go through to get to that endpoint. The actual output is nearly identical. Everything you said, sure, true.

00:41:16.56 [Tim Wilson]: However, flip side, I mean, one, it wouldn’t be the same. because it’s likely a much more involved and more data sources. But recognizing a process of saying, I have a request, and I would say probably you want to define that when a request comes in, I need to establish kind of the level of effort and some form of the requirements, like in a macro process. So processes can go higher to lower level. The adaptability, I think, is spot on. When Moe your question of like, what’s a process that I’ve seen work really well, I think work breakdown structures, not, I mean, they’ve been around for decades, come out of the project management world and people, they will bristle at them because the request is for you, someone to sit down and think through what the steps are gonna need to be. And it doesn’t have to be perfect. And 100% of the time, if somebody tries to just, estimate the level of efforts, and I think that’s 20 hours of work. And then if you take the same person and say, just make a list of everything that you think has to happen, and let’s just put some numbers on it, and all of a sudden it’s 60 hours. So that, I mean, I’ve worked at multiple, I’ve worked at consultancies that don’t have that, but that was much more individuals, but I would still make that list. If I’m gonna estimate something, whether or not I ever told the client I was doing it, I would make my full on

00:42:50.22 [Moe Kiss]: So, I think that is a… Sorry, but why wouldn’t you share that with a client out of curiosity?

00:42:56.43 [Tim Wilson]: Kind of back to Michael’s point. Sometimes they don’t… I mean, I may or I may not. Well, sometimes I don’t want to because I don’t want them diving in and saying… I’m going to miss on every one of those. The expectation is that if I have enough detail, I’m missing high and I’m missing low on enough different ones that it nets out to the reality. You start putting that level of detail in front of somebody who they’ve hired me to be the expert. If I say, I think this is going to take me 60 hours and they say, whoa, we can have a discussion and I can hit kind of the big points of you know, why it would, if they look at every line item and say, what do you mean this is going to take you two hours to review this document? And all of a sudden, we’re having a pointless discussion. So I see that as a more useful, and I’m trying to think when I worked.

00:43:47.76 [Julie Hoyer]: Or they want to rip out line items of like, oh, well, we’ll take that off your plate. And they want to then like hem and haul over splitting up the work. I’ve run into that too.

00:43:56.39 [Val Kroll]: And they’re like, well, then I’ll add in more hours after that to make up for what you aren’t going to do.

00:44:02.26 [Tim Wilson]: So I think from a process for estimating the scope, and then I would even say on the dashboard example, I am going to have a heavy bias towards doing. The process I will have will be as part of that discussion doing some formal wireframing because of the risk that’s opened up regardless of where it is that they’ll start Frankensteining what you’ve done and having some sort of an interim step. But it’s kind of like a general one from an intake of a project of a certain scale. Or saying, this is an ad hoc request. Whatever the threshold is, this is going to take less than four hours. I’m not going to say that I’m going to open this tool and pull that tool and do that query. There’s back to adaptability and judgment in it. But that’s just my simple answer to where’s a process that works well. I think scoping. work, having some steps and tools and having people understand how to use them. And if somebody’s a savant and says they nail it every time just off of their gut, it’s a weird thing for them. How do you, how do they prove that? How do you prove that out?

00:45:12.69 [Val Kroll]: But just coming back, I don’t think we ever resolved your thread, Tim, on like what happens when the scope blows up after you start digging into it. So like you’ve, best laid plans, you’ve got the WBS and right there’s rounding you’re in there, but you realize like, oh, shit, that’s actually not the data mart where that was. And some people was called to exactly which situation I’m referring to. Um, but like, when do you want to like talk about how you, cause I don’t have an answer. I just want to hear someone answer it. So is it you Tim or something else, but like, how do you,

00:45:44.90 [Tim Wilson]: Mine is simple. I’m like, communicate early and often and say, I’m sorry, we missed on this. What should we do? And we need to rebalance as opposed to try to hide it.

00:45:54.10 [Val Kroll]: But do you change the process then going forward? Tim, I’m curious. That’s the part I was…

00:45:58.58 [Michael Helbling]: not unless it’s happening a lot, because that’s where I get nervous that it’s a typically, for me as a consultant, I usually bake into the process what we’re gonna do if we run into something like that. So in other words, if we run into a situation where it’s gonna be like that, we’re gonna come to you and have the conversation and then we’ll figure out what we do about it. So it’s not like a, you know, obviously we hope it doesn’t happen very often, but it does happen. And then you just go talk about it. And honestly, I’ve had in my career, like, A lot of those conversations, I think maybe 20% end up with frustrated clients. Usually people get over it pretty quick and they get back to productivity pretty quickly. And honestly, a lot of times people are thankful that you brought it to their attention and were upfront about it and reset expectations correctly. I think what I’ve observed over the years is there’s a lot of people out there who try to fake it all the way to the end and people have gotten back a lot of bull crap. from people who they thought were going to give them something of value. So, in a certain sense, you stand out if you’re just honest about it and have a frank conversation. Honesty is the process.

00:47:12.67 [Val Kroll]: Yeah.

00:47:14.70 [Michael Helbling]: Yeah.

00:47:15.26 [Tim Wilson]: Well, that’s part of the process.

00:47:16.80 [Val Kroll]: I think so. You think adaptability is the first thing that you think about, Michael, for an effective one. And the ones that I’ve seen work well to go back to your question, Tumo, is all about expectations. And so, Are the expectations of me clear? Are the expectations, you know, to my stakeholder clear, the other people have to touch the part of the process, do they know? And so I think that kind of goes in line with what you were sharing there and communication. But Julie, we have to talk about assumptions though, going back to the document because that’s- That was the one that was there. We have to get back to that. Just tell us, tell us Julie, all about that and how that’s helped.

00:47:49.05 [Julie Hoyer]: Well, I was going to say like the assumptions one is big because if we were the example that Tim was just walking through and something like blows up, it’s because we assumed that like data would live in a certain place and we would have easy access to it. Everyone assumed and signed off based on that. And so that document value that you didn’t mention that we talked about multiple episodes. It’s so simple, but it really does save us a lot of pain because one of the sections we put in there was assumptions. We have started to bake in general assumptions that we will list, that the data listed above is available where expected. You can put those safeguards in, so then it’s like a soft contract almost with the client to say, for even just an analysis within a larger program that we’re working on with a client, we can say, hey, this analysis, this is the exact scope. These are the steps we plan to go through. These are the deadlines and rough timing that we’re going for under that these assumptions are true. The client, we talk about it, they have their expectations set, we’ve agreed on it. And it is where we come back. And if they, if we find something that goes against those assumptions, like it’s a very neutral way to bring it to them of like, we all agreed on this, now the terms have changed. So let’s reset. And they’re usually much more receptive to it. Or if they come with last minute requests, it’s kind of the same thing like, well, we, you know, agreed upon this. If you really want to change the scope, then we have the right to change the deadlines, right? Like you can’t, changed what’s in here with no effect to the other areas, which is kind of nice. So the assumptions have been like a saving grace, even though they felt so obvious in the beginning. I found it was a really good exercise. The more I thought through like, what am I actually assuming in my head or from experience and pain points? What do I know I should list out as an assumption that I might run into?

00:49:47.01 [Michael Helbling]: Yeah, experience is a good teacher on that too. So you pick stuff up and then you make sure to add it in as assumptions later. Definitely.

00:49:55.09 [Julie Hoyer]: Especially if you have points where you know that the client or your stakeholder is going to be a bottleneck. I like to list those out. This is based on the dependency that you guys are able to provide XYZ by such and such time.

00:50:08.72 [Tim Wilson]: Oh, I’ve totally done that. When they’re like, oh, we can get that data for you. That’s available. You can’t access it. It’s in, yeah, yeah, well, that’s easy. We can get that data. It’s like, OK, the assumption is going to be that you will get that data. I’m wondering if Moee’s got a reaction. On data science projects or on other projects, do you run into cases where… Do you document assumptions or… The projects where the scope is risky, how do you… Manage? Is it setting expectations? Is it documenting assumptions? Is it frequent check-ins? Is it all of the above?

00:50:46.41 [Moe Kiss]: There’s definitely documentation of assumptions. I would also say in most cases, those assumptions would be stress tested. Not always with the folks that you think, we will often use finance for stress test assumptions, which might surprise some folk, but often because it’s to do with our marketing strategy, which is also part of our global strategy. We will work with finance about how we thought about this particular market correctly or our investment here. This is how we’re thinking about it. Does that make sense, essentially? My preference is always to include assumptions. If not in the body of the doc, but at least in the end of the doc, I’m pretty ruthless on that. But yeah, that’s definitely a part of it.

00:51:39.20 [Tim Wilson]: But that’s a simple little potential step of the process. It’s two things. It’s one, having somebody check the assumptions, do they seem reasonable? Are there assumptions that are missing here? Those may be two different parties or you may ask the same. I don’t think too often of actually checking the assumptions with a third party, but that makes going to the team that actually has that say, hey, we assume we’re going to be able to get this data and this form from this, and that’s going to be reasonably straightforward. We want to check that assumption before we commit to doing this, asking finance a question. I don’t think I’ve done that, but now I want to.

00:52:25.64 [Moe Kiss]: Oh, I see what you mean. I think it’s a little bit different internally though, right? Because have I got it right that when you say, you check an assumption of like, does this start exist in this place? Yada, yada, yada, you’re going to clients. Whereas like, it’s very different for our team because we could just look it up. So like, I don’t know if there needs to be the same rigor on that specifically.

00:52:50.21 [Tim Wilson]: Plenty of in-house cases where they’re too different. I’m thinking pharma, you’ve got a marketing analytics team, and you have a commercial insights team. They’re the same company. They roll up to the same, but boy, there is an assumption that I mean, even though I’ve been working with those sorts of teams externally, it’s the internal people that say, well, oh, yeah, you’ll have to go to this other internal team to get that. And it’s like, well, your internal can’t you reach out. They’re like, we can reach out, but it doesn’t matter. They’re not going to.

00:53:21.20 [Moe Kiss]: But I think a lot of that happens informally, firstly. But secondly, I think what I find with the folks in our team, it’s less assumptions about whether something exists and it’s more about how it’s calculated. So whenever we have a table or whatever, there will always be a readme that explains it. But some people write really shit, readme’s, that make it really difficult to understand how that metric is actually calculated. And sometimes they’re like, the amount of precision or ways it could be misinterpreted. That very much happens, I would say, informally, where folks, you can see who the coder is, you would go to the coder and be like, am I thinking about this metric correctly? I would say that it’s completely informal, but I also am not doing the work, so I don’t know. I don’t think that would be documented.

00:54:09.88 [Tim Wilson]: I’ve, again, watched teams where they’re like, oh, we have this. One team says, well, there’s this flag in this data, which is the same thing that’s like a segmentation flag. And it’s like, well, what is that actually? We assume that it means these things. And they’re like, yeah, yeah, we think that’s what it means. It’s like, but do you know? And you may find out much later in the process that, oh, you had an assumption or maybe business stakeholder had the same wrong assumption and it’s only somewhere down the path that because something looks funny and they go to another internal team and they’re like, well, that’s not what that means at all. So I think it’s going to vary. I’m clearly now obsessing about one specific client that was just constantly triggered. Internal teammate didn’t know what internal team B was doing, and that was also had some very sensitive data. But then you’re, I think there’s a spectrum all in those lines, but any sort of assumption, you know what, Julie, like you were calling, our assumption is we have an assumption that at these checkpoints, we will get feedback from you within a couple of days. I mean, there are assumptions that are sort of setting expectations for what the, the business partner will do that is saying, we’re assuming this will happen and it’s kind of a way for them to say, well, yeah, you can do that except for I’m going to be on PTO for three weeks. It’s like, well, I’m glad we validated that assumption because that’s going to make it hard to pull this off. Yeah, we’ve all got one of those.

00:55:42.84 [Michael Helbling]: All right, we need to wrap up. I’m gonna throw all of you a big curveball right at the end, which is this. Everything we’ve just talked about matters even more now because of AI.

00:55:57.92 [Moe Kiss]: Man, no. I mean, AI is really good at process. I just think it’s very good at.

00:56:03.84 [Michael Helbling]: No, you have to understand your process and manage it effectively to be able to incorporate AI effectively.

00:56:10.99 [Tim Wilson]: No, it’s always fucking mattered. And now, sure, if people want to say, well, now with AI, you’ve got to do it more, it is always mattered.

00:56:18.17 [Michael Helbling]: You do. I’m just saying it has always mattered. But now people want to leverage things like AI, and it’s not going to work unless they have their process in place.

00:56:27.90 [Julie Hoyer]: So Michael thought that was going to be a nice closing and instead of Tim just agree with me.

00:56:37.90 [Michael Helbling]: You know, you want to. All right.

00:56:42.25 [Val Kroll]: Well, I would Michael, you said earlier, you disclosed that you’re a person who doesn’t document your process. So I could see where you’re coming from on that comment.

00:56:52.32 [Michael Helbling]: I’ll leave that there. Yeah. As you try to work with things like AI, it forces you to be like, oh, I need to extrapolate my process out more cleanly if I actually expect the AI to perform in the way I want it to. It’s a thing that opens your eyes to, OK, yeah. Whereas before I could just.

00:57:16.18 [Tim Wilson]: Those poor, those poor humans. Yeah. Those poor fucking humans who were reporting to you or like driving driven up the wall. That’s why I said, I’ll leave it there.

00:57:22.65 [Tim Wilson]: And you’re like, but now it’s important. I could just yell.

00:57:27.05 [Michael Helbling]: I could just yell at them, Tim. Yeah. And they’ll change your behavior. You can yell at the AI. It’ll change his behavior and tell you how awesome you are. The AI will be like, oh, I can see how angry you are about that first thing. I’ll do that. But I’ll still make the exact same mistake over again. Anyways, all right, we need to wrap up. And if you’ve been listening to this show, I’m sure you have your own thoughts about process and its place in our world of analytics. We would love to hear from you. And the process for doing that is reach out to us on the Measure Slack chat group or on LinkedIn or email at contact at analyticshour.io. And I don’t know if all of you know this, but we’ve been putting our shows up on YouTube as well as we’ve started putting out little snippets and shorts of like little parts of the show that you can find on our YouTube channel at Analytics Power Hour on YouTube. So go subscribe and like the videos. That’s a thing we want you to do for us. That will help our process.

00:58:30.55 [Moe Kiss]: That will help our KPI. That helps YouTube. Sure.

00:58:33.86 [Michael Helbling]: That will help. That helps YouTube’s process of promoting us to more listeners out there, which then helps you by exposing you to the network and wonderful community of analytics people that all our fans of this show, which we appreciate. All right. And of course, I think I speak for all of my co-hosts with the exception of Tim. No, I’m just kidding. But I say that no matter what your process, keep analyzing.

00:59:08.16 [Announcer]: Thanks for listening. Let’s keep the conversation going with your comments, suggestions, and questions on Twitter at @analyticshour, on the web at analyticshour.io, our LinkedIn group, and the Measure Chat Slack group. Music for the podcast by Josh Crowhurst. Those smart guys wanted to fit in, so they made up a term called analytics. Analytics don’t work.

00:59:32.68 [Charles Barkley]: Do the analytics say go for it, no matter who’s going for it? So if you and I were on the field, the analytics say go for it. It’s the stupidest, laziest, lamest thing I’ve ever heard for reasoning in competition.

00:59:45.91 [Michael Helbling]: And it’s making a bald spot on top of my head. And… That’s what’s making the bald spots? So, yes. Yes, Moe. That is what’s making it.

00:59:55.01 [Moe Kiss]: I can’t even tell a fucking joke because it’s like 30 seconds delay and you’re all frozen, so I don’t even know if it was funny.

01:00:02.17 [Val Kroll]: Uh, well, we are laughing. Yeah, it was funny. I’ll be good for the shorts.

01:00:12.78 [Moe Kiss]: I used to cry about analytics all the time.

01:00:22.08 [Val Kroll]: Still do. I have a shirt that says I can cry at work. I wear it on stage.

01:00:29.67 [Tim Wilson]: This is not a fucking EQ episode. What the hell? I’m about to have internet issues. Just to get out. You guys are breaking it up. What is this?

01:00:41.28 [Michael Helbling]: Now it’s my turn. Let’s do a quick 20 minute episode about process and call it a day.

01:00:50.11 [Val Kroll]: That’s all the time we have.

01:00:53.49 [Michael Helbling]: Oh, look it up. Jump right into it.

01:00:56.34 [Val Kroll]: Keep crying about it.

01:01:03.18 [Moe Kiss]: It feels weird that I’m the only one who’s drinking.

01:01:14.64 [Tim Wilson]: Rock flag in its process all the way down.

01:01:23.05 [Val Kroll]: Sorry, I laughed on top of that.

It’s turtles all the way down … of course. 😉